NOE (Nuclear Overhauser Effect) is an important NMR measurement technique that can reveal spatial proximity relationships within molecules. In this column, we discuss the difference between difference NOE, 1D NOESY, and 2D NOESY, and how to select each method, the relaxation time that is key for analysis. The causes and solutions for cases when NOE is not detected are also covered. Moreover, we answer the frequently asked questions and explain the key points for effective use of NOE measurement.

What is NOE measurement?

NOE measurement (Nuclear Overhauser Effect) is a method to observe nuclei in spatially close distance. The NOE measurement is utilized to obtain stereochemistry of molecules, and distinguish isomers and confirm location of substituent group, for application of small molecular compound.

Principle of NOE

The NOE is a phenomenon where spatially close nuclei magnetically affect each other and cause an NMR signal intensity change.

1. Relation between nuclear spin and magnetic field

When placed under the influence of external magnetic field, the energy state of nuclear spin of proton splits (Zeeman splitting).

2. Saturation by radio wave

When radio wave continues to irradiate to a specific proton, the spin state of the proton "saturates". In saturation state, energy absorption and release are balanced, and the signal disappears.

3. Dipole - dipole interaction

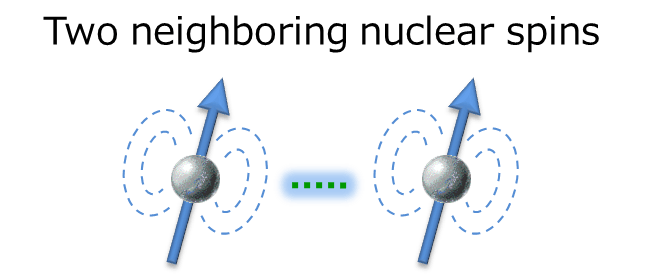

When saturated proton magnetically interacts with another spatially close proton, the signal intensity of this proton changes. This interaction is classified as "bipolar-bipolar interaction".

Considering NOE, we think about two protons in one molecule as shown in the above figure.

When these protons are close to each other, the NOE is observed due to dipole interaction.

On the other hand, if the distance between protons is far, the NOE is not observed as there is no dipole interaction.

It is known that the dipole interaction is closely related to the inter-nuclear distance and molecular mobility, and if the distance between two nuclei is shorter than 6 Å, NOEs may be observed.

On the other hand, since the magnitude of the interaction is proportional to the inter-nuclear distance (r) to the minus sixth power (r-6), When the inter-nuclear distance increases, the interaction rapidly decreases, making it difficult to observe NOEs.

How to observe NOE

Different from the splitting by spin-coupling, the NOE is not observed with the NMR spectrum (1D, 2D NMR) that we have introduced so far.

Therefore, the following steps are required for the NOE measurement.

- Irradiating radio wave to specific proton (excitation/saturation)

- Observing signal intensity change of other protons

- Judging if this change is coming from the NOE

Types of NOE Measurement

There are three main types of NOE measurements.

- Difference NOE: observe a steady state NOE by taking the difference in spectra with and without radio wave irradiation.

- 2D NOESY: observe transient NOE by using a 2D spectrum.

- 1D NOESY: selectively excite protons and observe transient NOE in one dimension.

Steady state NOE is to irradiate a radio wave for a long time, make a specific proton saturated, and observe the signal intensity change of other protons once the saturation state becomes steady.

Transient NOEs are observed during the mixing time after the spin state is temporarily changed by a short period of radio wave irradiation. Since the mechanisms by which NOEs are generated are different, the measurement conditions for each method must be determined by considering the characteristics of each.

Difference NOE Measurement

Difference NOE measurement is a method of checking the change in signal intensity of nearby protons by taking the difference between the spectra of a specific proton when irradiated with radio waves and when not irradiated with radio waves.

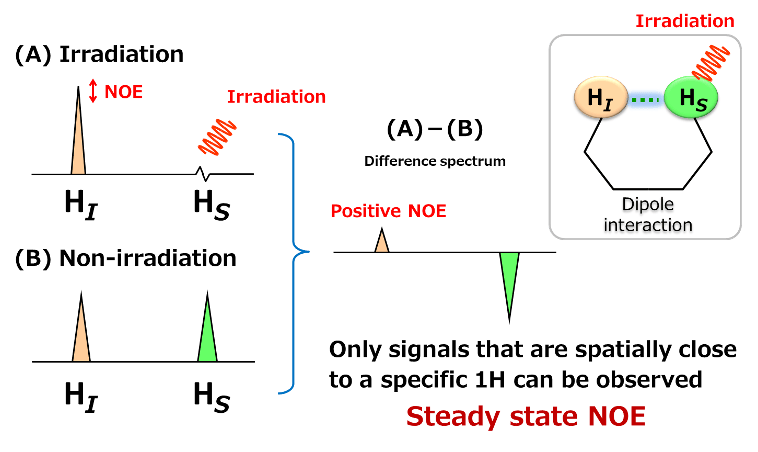

As shown above, two protons, HI and HS are going to be considered. HI and HS are in spatially close distance and having a dipole interaction.

(B) is 1H spectrum when HS was not irradiated.

Here, when a radio wave is irradiated to HS to saturate HS, the signal of HS becomes invisible. At this time, the signal intensity of HI becomes large due to the dipole interaction between HI and HS. This is the "Change due to NOE". Since the change of signal intensity by NOE is very small, the difference between (A) and (B) is calculated to make the difference clear. The NOE observed by difference NOE is called "steady state NOE". In general, for a small molecular compounds having high speed molecular motion in solution, when the signal change of irradiated proton is expressed downward, the NOE signal is observed as an upward signal. This is called "Positive NOE".

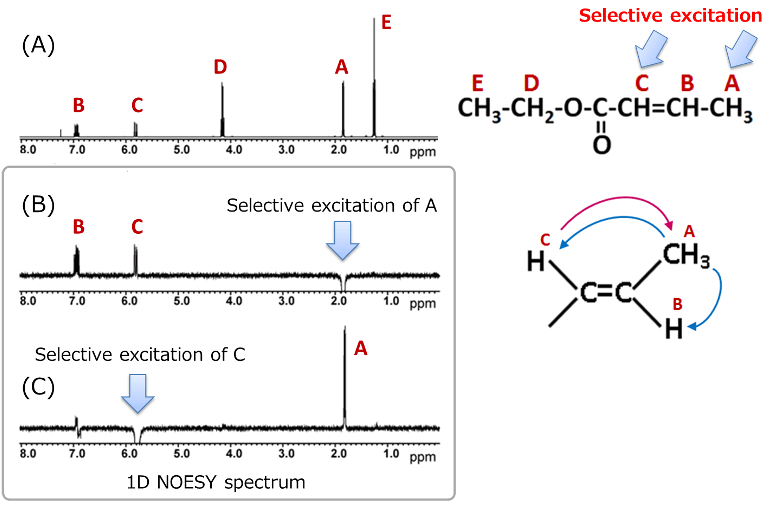

Actual example of difference NOE measurement is introduced, by using ethyl crotonate.

We would like to determine whether the conformation of a double bond is cis or trans by using the difference NOE measurement. The proton of methyl group expressed as A is irradiated, and the related NOE is observed.

In the upper part of the above figure, the 1H spectrum of ethyl crotonate is shown. In the lower part, difference NOE spectrum when a proton of methyl group at A is saturated, is shown. This data is measured by using 400 MHz instrument and the NOE signals are observed upward at B and C.

Based on the obtained results, irradiation of the proton of the methyl group at A led to observable NOEs at B and C, indicating that ethyl crotonate has a trans conformation.

1D NOESY

1D NOESY is a method to selectively excite a specific proton and observe the transient NOE between the specific proton and the other spatially nearby protons as a one-dimensional spectrum. In this measurement, soft pulse (narrow bandwidth pulse) and pulsed field gradient are used to excite only the proton of interest, and the change in NOE over the mixing time is recorded. Since there is no need to subtract spectra as in difference NOE, spectra that are easy to analyze are obtained. 1D NOESY is suitable when you have a specific proton of interest or when you want to check the NOE in a simple way.

Here, we present an example of a 1D NOESY measurement using ethyl crotonate. The (B) in the above figure shows 1D NOESY spectrum obtained by selective excitation of proton A, while (C) shows the spectrum obtained by selective excitation of proton C. Unlike difference NOE spectra, 1D NOESY does not show the residual signals caused by subtraction of two spectra obtained before and after radio wave irradiation, making the spectrum easier to analyze.

The interpretation method is similar to that of difference NOE: we check how other signals appear when the selectively excited proton signal is shown downward.

In example of ethyl crotonate, when proton A is selectively excited, positive NOEs are observed at B and C. Conversely, when proton C is excited, a positive NOE is observed only at A. These results also support the estimation that ethyl crotonate has a trans type stereochemistry. Thus, when determining stereochemistry with ambiguous spatial arrangements, it is important to measure 1D NOESY of the selective excitation of each part.

2D NOESY

2D NOESY is a method to observe interaction (NOE) between spatially close protons in a molecule as a two-dimensional spectrum. This experiment observes the appearance of how NOE changes (transient NOE) during the mixing time after temporarily changing the proton spin state. The obtained spectrum expressed the self-signals on a diagonal and correlated signals between spatially close protons. Since the 2D NOESY allows for comprehensive NOE correlation in the entire molecule, it is suitable for analysis of complicated structures and confirmation of entire signal assignment.

From here, we will explain how to read 2D NOESY spectra. As shown in the above figure, when A and C, B and D are in close proximity to each other, such correlation signals appear. The data sliced at positions A and B (in blue dotted line) in X-axis direction, are equivalent to 1D NOESY spectra by selective excitation of A and B, respectively.

This figure shows 2D NOESY of ethyl crotonate. Looking at each sliced data, the signals at the selective excited part (in red) appear downward, while signals with NOE correlation (in black) appear upward (positive NOE).

When looking at the correlation signals in black, the following NOE correlations can be found:

A:B and C

B:A

C:A

D:E

E:D

In addition, focusing on the NOE correlations among A, B, and C, the results support the presence of the trans type conformation, consistent with the previously mentioned difference NOE and 1D NOESY results.

Easy guideline in selecting NOE measurement method

As we have explained, for an NOE measurement, it is possible to choose the method according to the purpose. We recommend that you begin with 1D NOESY which allows for easy condition setting and clear spectra to be obtained.

Target proton has been specified: 1D measurement

Want to see NOE across the molecule, or signal assignment is uncertain: 2D NOESY

Important factor for NOE measurement: Relaxation time

One of the most frustrating problems in NOE measurements is, without a doubt, "when no NOE signal is detected!" In such a case, please measure the longitudinal relaxation time (T1) of the target sample, first. Then, for difference NOE measurement, please set the irradiation time of the excitation pulse to be more than 5 times that of T1 of the target sample. Also, please set the mixing time with 1D/2D-NOESY, to be about 0.8 times that of T1 of the target sample.

Now, why do we need to consider the relaxation time of the target sample, for an NOE measurement? This is because NOE has a deep relationship with relaxation time, as NOE is a relaxation phenomenon based on the dipole interaction.

Here, we would like to provide a simple explanation about relaxation in NMR.

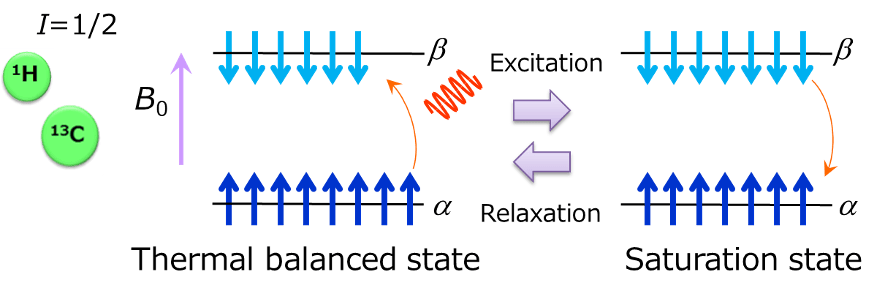

The above is the schematic diagram of energy levels of nuclear spin of spin number= 1/2 when it is placed in a static magnetic field. Nuclear spin takes up two energy states after undergoing Zeeman splitting by being affected by magnetic field. Stable state with low energy is called α state, while the one with high energy is called β state. When a radio wave having a frequency equivalent to this energy gap is irradiated, the spin in the α state absorbs the energy of radio wave and excited into the β state. When the spin number of the α state and the β state becomes the same by irradiation of a radio wave, energy absorption stops, which is called the saturation state. In the saturation state, the spin in the β state emits energy and returns to the α state, finally, it even returns to the thermal balanced state. The whole process is called relaxation. Then, a series of processes from excitation to relaxation, are called the NMR phenomenon that we are observing.

The interaction works between two neighboring nuclear spins, which is the driving force for the relaxation explained earlier. In solution NMR, the dipole interaction is one of the major factors in promoting relaxation. Therefore, setting the parameter of relaxation time which has deep relationship with dipole interaction is an important key for successful NOE observation.

Cause and solution for undetectable NOE signals

The likely cause and action when NOE is not detected, are explained in the following 4 points.

- Optimize sample adjustment/measurement conditions

- Change molecular motion

- Change resonance frequency

- Change measurement method

First, check if 1. is optimized, and if the NOE is not observed, try 2 to 4.

1. Optimize sample adjustment/measurement conditions

Since the NOE signal is very weak, the result is greatly affected by the sample concentration and purity, and measurement condition setting.

- Concentration: if the concentration is too high, relaxation tends to occur between molecules, weakening the NOE.

- Caution against contamination of paramagnetic substances: dissolved oxygen and metal ions (Fe, Cu, etc.) promote relaxation, thus preventing NOE.

- Setting of irradiation/mixing times: Based on T1(longitudinal relaxation time), irradiation time of more than 5 times, mixing time of about 0.8 times are guidelines.

2. Change molecular motion

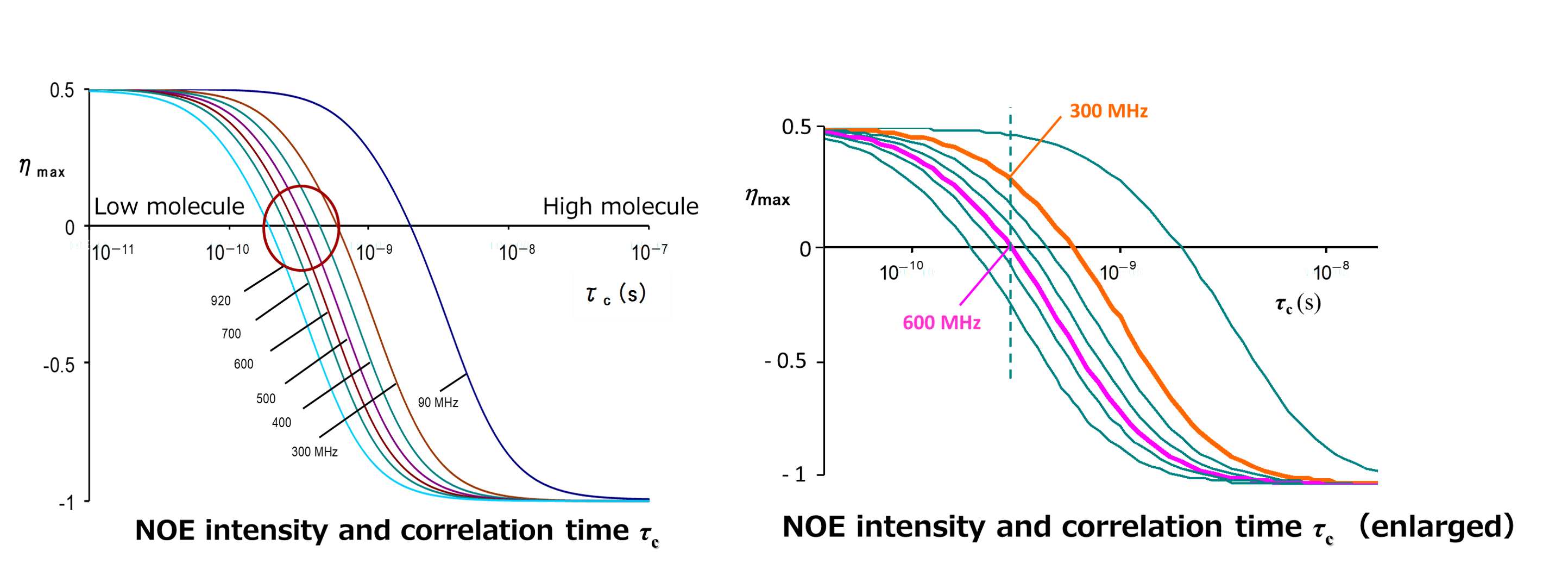

The intensity of NOE also depends on molecular motion. The following graph shows the relationship between NOE intensity and molecular motion.

This curve was theoretically brought from the relational expression of NOE intensity and dipole interaction.

The vertical axis expresses the NOE intensity, while the horizontal axis expresses the product of observation frequency ω multiplied by correlation time of the molecule tC. tC is the time required for a molecule to make a full rotation in solution and is a parameter expressing the motion of the molecule. Which means, the smaller the molecule is, the shorter the tC becomes. The larger the molecule is, the longer the tC becomes.

The left shows the region of low molecule where tC is short and the motion of molecule is fast. Here, a positive NOE is observed. On the other hand, the right shows the region of polymer where tC is long and the motion of the molecule is slow. Here, the negative NOE is observed. Which means, the graph indicates that NOE intensity greatly changes depending on the motion of the molecule.

What matters in performing measurement is that there is a region where NOE becomes zero. When the molecule is close to the region where the product of multiplication of observation frequency ω and correlation time of the molecule tC is 1, the NOE becomes very weak or the NOE is not observed.

Therefore, if NOE is not observable even if measurement conditions are reviewed with your instrument, it is possible that the product of multiplication of observation frequency ω and correlation time of the molecule tC is in this region.

In such a case, changing ω or tC is a possible choice. However, changing ω means changing the measurement magnetic field, and it may be difficult to try it at once if you hold only one instrument. Therefore, we suggest that you consider changing tC , which is, changing the factor that can affect tC(measurement temperature and viscosity of a solvent). We recommend that you change the measurement temperature, first.

3. Change resonance frequency

Next, I will explain the case where the observation frequency is changed, which is, where the measurement magnetic field is changed.

The above figure shows the magnetic field dependence of NOE intensity and correlation time tC .The vertical axis represents NOE intensity, while the horizontal axis represents correlation time tC. Each curve corresponds to a magnetic field from 90 MHz to 920 MHz. The curves shift to the left as the measurement magnetic field increases. If we focus on the tC at which the NOE becomes zero, we can see that the point at which the signal intensity becomes zero shifts to the region of low molecules (where the molecules are in fast motion) as the magnetic field is increased. This means that under the same measurement conditions, the signal intensity of positive NOE becomes weaker at higher magnetic fields. For example, it can be said that a molecule with zero NOE in a 600 MHz instrument may have a positive NOE observed in a 300 MHz instrument. In addition, for the case of a molecule with about 1000 molecular weight, the possibility is high that it can be in the region in a circle where NOEs are extremely small, so attention is needed.

4. Change the measurement method

If NOE is not observed after trying methods 1 through 3 introduced so far, a measurement method called ROESY is used. ROESY is a NOE measurement in a rotational coordinate system.

The above figure is the 1D NOESY and 1D ROESY spectra of gramicidin S measured at 90°C. At this temperature, the NOE of gramicidin S becomes nearly zero, but using ROESY allows the observation of correlation signals. The NOE observed in ROESY is referred to as ROE. The greatest advantage of ROESY is that, as illustrated in the schematic diagram, ROE is always positive and does not have a zero region. You might wonder, "Then why not just use ROESY from the beginning?" However, ROESY requires more careful parameter settings and tends to produce unwanted signals. Therefore, ROESY is better used when NOESY does not work well.

Frequently Asked Question about NOE Measurement

In difference NOE measurements, if the irradiation position is not set at the peak maximum, spin coupling effects can occur, causing changes in the signal shape. Therefore, the irradiation position should be set precisely at the peak maximum.

In difference NOE measurements, when multiplets more than doublets are selectively irradiated and if the irradiation position is shifted from the peak maximum, the signal shapes are changed. The two spectra above show difference NOE results when the methyl group protons of ethyl crotonate are irradiated. Positive NOE signals are observed at B and C. If the irradiation position is shifted to around the center ppm of signal A instead of the peak maximum, a large, asymmetric, residual-like signal appears, as shown in the dotted area of the top spectrum. This is due to spin coupling interactions with proton B. Always select the irradiation position at the peak maximum in difference NOE measurements.

This phenomenon is known as indirect NOE (three-spin effect), and in small molecules, it can be observed when protons are arranged nearly linearly.

Normally, small molecules undergoing rapid motion in solution exhibit positive NOE signals. However, signals may sometimes appear in the same direction as a negative NOE. For example, consider the spatial arrangement shown in the figure on the left, where protons A-B, and B-C are spatially close, but A-C are far apart. The figure on the right shows a 1D NOESY spectrum when proton A is selectively excited. Since A and B are close, a positive NOE is observed at B. However, an indirect NOE may also appear at C via B. This indirect NOE appears in the opposite direction to the positive NOE. It's important to note that this signal does not indicate that A-C are spatially close. This phenomenon is most likely to occur when the three protons are arranged nearly linearly in space, and it is known as the "three-spin effect."

When, three protons are arranged spatially special, NOE may not be observed even if the distances are close.

As a special case of the three spin effect, let me explain the triangle problem. As shown in the above figure, when three protons are arranged spatially special, this problem can occur.

When A is selectively excited, not only the distance between A and B, but also A and C are close. Thus, positive NOE is supposed to be seen between A and C, the forecasted spectra is the right in the above figure.

However, the positive NOE from A to C shown in orange and the indirect NOE via B shown in green can cancel each other out, resulting in no observable NOE. Theoretically, this cancellation occurs when the ratio of distances between each pair of protons is 1:1:1.26. In other words, even if the protons are spatially close, NOE may not be observed.

Reference

- Claridge, D.W.T.(2004), *Yūki kagaku no tame no kōbun Kainou NMR tekunikku* [High-resolution NMR techniques for organic chemistry] (T.Takeuchi & M. Nishikawa (Trans.) Kodansha Scientific.

- Fukushi, E. & Sohmiya H. (2007), *Korenara wakaru nijigen NMR* [Understanding 2D NMR made easy]. Kagaku Dojin.